Improv as a Healing Art: What Polyvagal Theory Teaches us about Why Improv Works

If you’re involved in the improv world, you’ve likely heard people talk about the healing power of improv, whether they’re joking about improv being “their therapy,” or reflecting on the transformative impact they’ve seen it have on others in theatrical and applied settings.

This article is the first installment in a series that explores simplified interpersonal neurobiology that gives us a concrete way of understanding why improv works.

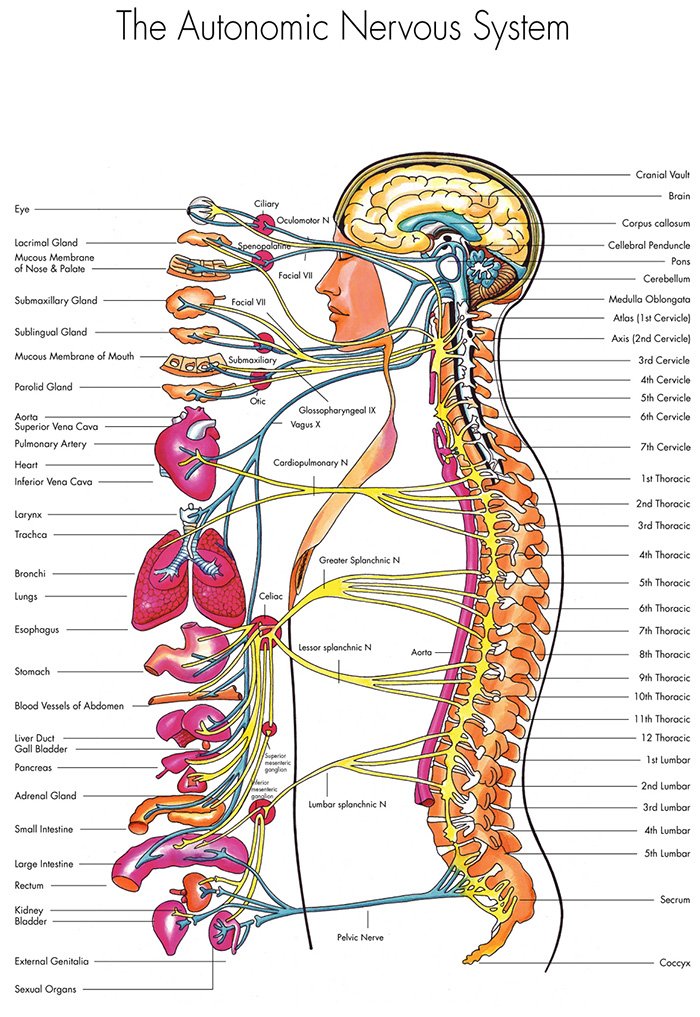

Autonomic Nervous System Basics

Our bodies carry out many functions (heart rate, breathing, digestion) without us having to mindfully cue them to occur. These functions are regulated by the autonomic nervous system, which serves as a “control center” for many of the automatic functions of our body.

Just like our heart beats on its own, without needing our mindful instruction, there are other systems that operate below the realm of conscious thought that impact the way we process and respond to the world as we encounter it. Stephen Porges, MD coined the term Neuroception to describe when our nervous system detects and responds to cues before we have cognitive awareness of them. (A)

To understand Neuroception, imagine a time that you were startled. Your body likely responded physically before your cognition (thoughts) caught up. You didn’t have to tell your body to tense up, or to change your breath - your body did it automatically.

These types of responses happen all the time (sometimes more subtly, sometimes more intensely), and our autonomic nervous system is constantly learning to toggle our response system based on what we encounter and how things unfold. This part of our brain learns to manage risk, keep us safe, and create patterns of connection by changing our physiological state. (B) Neuroception is ultimately driven by a biological drive to survive.

In simple language, this means that our autonomic nervous system impacts the way that our body and brain responds to our experiences. In turn, this impacts our feelings, how we connect with others (or don’t), and our general state of being (do we feel shut down? social? safe? ready to fight or flee?)

Understanding more about what is happening “behind the scenes” in our body unlocks a new understanding of the way we move through the world. As noted by Bloch-Atefi and Smith (2014) “our navigation of the world is inherently a mind-body experience,” and the more that we can understand the nervous system, the more we’ll understand the story- and impact - of this connection.

The Polyvagal Theory (PVT) will help us further explain a slice of nervous system theory, and what this has to do with improv.

Polyvagal Theory basics

PVT can trace its roots back to some of Porges’ early work in 1969 with heart rate variability and a question about how the tone of the vagus nerve could be a marker of resilience and risk for infants. (A) In 1994, after many years of exploration, he presented the Polyvagal theory, which we’ll dive lightly into today.

You've probably heard that we have two branches in our nervous system: the sympathetic and the parasympathetic. The job of the sympathetic nervous system is to energize us to take action (fight/flight) in times of need by increasing our blood pressure/heart rate etc., and putting unnecessary functions (like the digestive system) on hold. The parasympathetic system was said to work in opposition of this to return the body to homeostasis when the perceived threat had passed.

Heavily simplified, Porges’ provides a more complex understanding of the ANS by identifying a three-part hierarchical system that keeps the sympathetic system, and details two distinct pathways of the Vagal nerve (very-important-nerve-super-highway that is the main component of the parasympathetic system):

The Dorsal Vagus: Brings us out of connection into immobilization.

The Ventral Vagus: Brings us into connection and co-regulation through the Social Engagement System.

He further delineated how these three systems work together, and outlined a coherent system of communication, regulation, and social engagement that operates within the autonomic nervous system. Within this system, he notes that the parasympathetic system is both our system for immobilization AND our system of connection - which extends beyond what we previously understood.

To help me explain this, imagine a ladder.

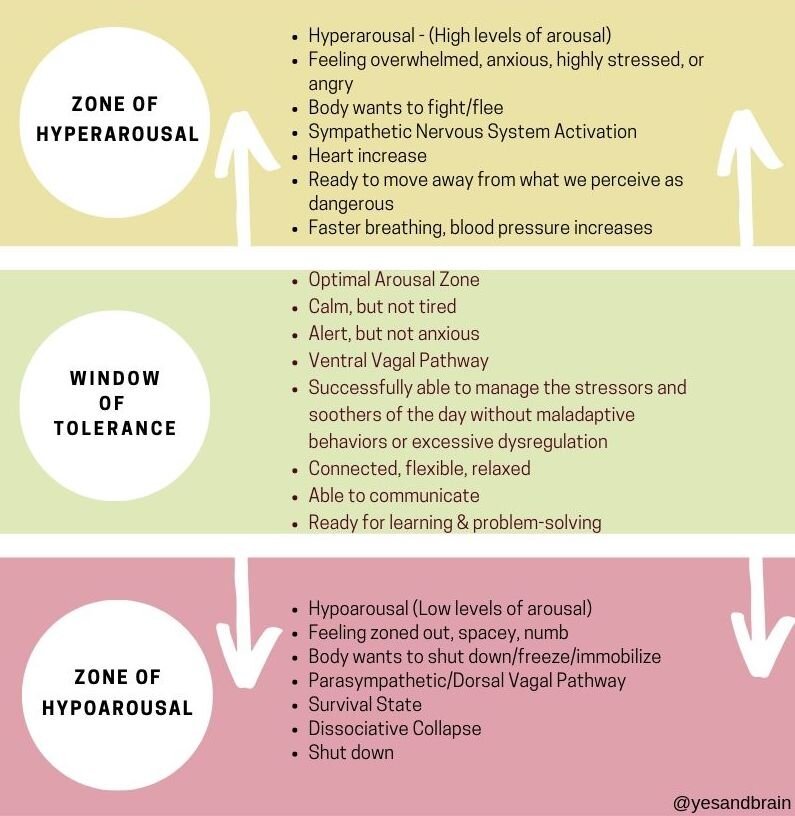

VENTRAL VAGAL PATHWAY - (TOP OF THE LADDER)

When we’re at the top of the ladder, we’re in the ventral vagus pathway and have activated our “social engagement system,” which is part of the parasympathetic system. When we’re in this state, we feel safe, we like being connected to others, and we communicate well.

Our heart rate slows down, we breathe deeply, we feel relaxed, we’re drawn to engage, our muscles relax, we use warm facial expressions and vocal shifts to drive our connection, and we can engage in learning, attention, and problem-solving. When we’re in this place, we’re likely to interpret minor stressors from the standpoint of being relaxed and safe, and we’ll recover quickly.

SYMPATHETIC PATHWAY -(MID LADDER)

When we pick up cues through neuroception that we’re not safe, our stress levels rise and we move down the Polyvagal ladder. This is when we slide into the sympathetic nervous system - which you may connect with “fight or flight.” When we’re in this state, we’re ready to mobilize, and our body gives us energy and strength to move away from whatever we’re perceiving as dangerous. However, you can still be in this state without following those impluses and physically moving your body.

When we’re in our sympathetic system, our heart rate and blood pressure increase, we breathe faster, stress hormones flood our body, pain tolerance increases, muscles get tight, we’re often louder and faster, and we can’t process complex emotions. While we’re not great at communicating in this state, we’re able to mobilize to deal with a crisis or possible danger, which certainly has value.

Just like when we’re at the top of the ladder, we filter what we encounter in this state through how we feel at the time. This means we may be quick to attack, blame, or judge - even when there isn’t a huge threat. We aren’t meant to spend a lot of time in this state, though some people’s brains do, especially if they have a history of trauma or adverse experiences.

DORSAL VAGAL PATHWAY (BOTTOM OF THE LADDER)

If we continue to feel stress, our arousal levels increase further, and we slide further down the ladder to the dorsal vagal pathway. As we do that, we land in “immobilization.” This is a survival state that we go to when we can’t escape and we feel helpless and overwhelmed. Even though this pathway sometimes gets called “freeze,” you can experience this state while moving your body.

When we’re in this state, we may have shallow breathing, have less speaking/language skills, a high pain tolerance, avoid eye contact or look down, not be capable of engaging in social exchange, and feel numb or hopeless. When we’re here, we may lose track of time, and our memory is only picking up bits and pieces - which is why trauma memories can be fragmented. The predominate feelings of this state are often shame, helplessness, and overwhelm —which is an inherently lonely experience.

The evolutionary job of this state is to give us a chance to escape if we’re hurt in a bad situation, or to die a relatively painless death if we’re in a situation that is heading in that direction. This state is also not meant to be somewhere we spend a lot of time (though trauma histories and adverse experiences may mean we end up here a lot).

THREE IMPORTANT THINGS TO KNOW:

1. These pathways operate in a phylogenetic hierarchy, which means that they’re rooted in the evolutionary development of our species. In simple terms, this means that if we look to the past, the vertebrae creatures that inhabited the earth way back in ancient times didn't always have all three of these systems, and our capacity to activate all three of these systems developed from the “bottom up” through the evolutionary timeline. (D) In a parallel manner, these parts of our brain also develop sequentially from the bottom up in utero.

2. We slide between these states in a specified order, which means that if we’re at the bottom of the ladder, we have to slide past the sympathetic system (and engage in a form of mobilization) in order to get out of immobilization (and vice versa).

3. Our life experiences shape the way that we move between these three distinct systems, and adverse experiences (like trauma) can result in our brain defaulting to an over-activation in the mid to bottom section of the ladder. Further, experiences like trauma can mean that we have a hard time navigating through these various states in a healthy way, and this may compromise our ability to recover when we do move into hypo or hyper arousal.

Even without a complex trauma history, it is common for all of us to have experiences that drop us in - and out - of regulation. Keep in mind that our sympathetic system can activate within a range. The person who singlehandedly lifts a car off of someone after an accident is activating that system - but so are the people who are snapping at their partner in a moment of stress, or people who feel like they endlessly spin in anxiety.

Depending on the experiences we’ve had, it may be hard to distinguish between different types of threat and the actual present risk. For example, someone who was abused as a child likely spent a good amount of time in the sympathetic and dorsal vagal pathways towards the bottom of the ladder. When their brain activated those pathways, that activation became associated with a cascade of physiological shifts, emotions, and experiences. Later in life, if those same systems are activated in a more benign situation, they may struggle to recognize that they’re not experiencing the same level of threat that they previously came to associate with those feelings.

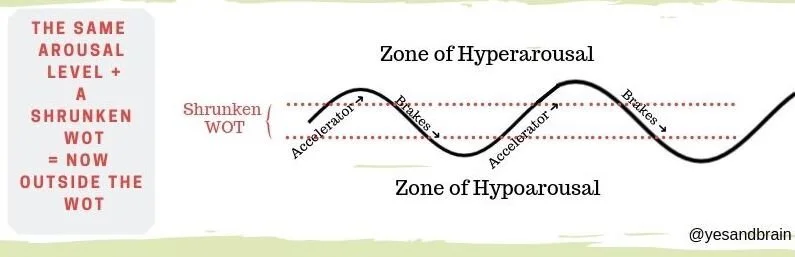

While our brain responding quickly to challenging situations is adaptive in trauma situations, it may mean that someone quickly moves into a place of fight/flight/freeze when the current situation doesn’t actually call for it. This may be reflected in having a “narrow window of tolerance,” which means that their ability to tolerate things without moving into hypo or hyper arousal may be limited. Minor stressors may result in a quick mobilization down the ladder, and the body may not be able to efficiently return to a regulated state once going there.

Once we have developed our natural patterns within this framework, shifting towards healthier patterns can also be challenging. For people who spend a lot of time at the bottom of the ladder, encountering the “mobilization” that comes with sliding towards regulation can feel really scary and cause a retreat back to the bottom of the ladder. Similarly, if someone lives in the fight/flight section of the ladder, feeling calm might actually feel scary, vulnerable, and unfamiliar - causing them to retreat back to the familiarity of mobilization.

So….what does this have to do with improv?

In short, a little bit of everything.

In long, PVT provides us with a framework to understand and bring awareness to the way in which we move through the world, and improv provides us with a perfect playground to connect with our patterns of physiological response and the corollary feelings and self-expression that impact our connections - or lack thereof - with others. As we develop awareness around our patterning, and engage in experiential learning, improv provides us with a powerful tool to explore embodiment, expand our window of tolerance, and find a space to understand ourselves, others, and our internal dynamics. Because this is happening within the context of relationships, co-creation, and connection with others, improv is fundamentally oriented around strengthening our social engagement system, which impacts our regulatory functions, health, and social connectedness.

6 specific ways that this occurs:

1. IMPROV PROMOTES RESILIENCE AND THE EXPANSION OF OUR WINDOW OF TOLERANCE THROUGH NEURAL EXERCISE

Steven Porges defines play as “reciprocal and synchronous interactions” that use the social engagement system as a “regulator” of mobilization behavior (e.g. fight/flight). He notes that as we engage in this face-to-face play, the neural regulation of our social engagement system improves, and we gain resilience in dealing with the challenging moments in our lives (M).

Let me break this down in simple language.

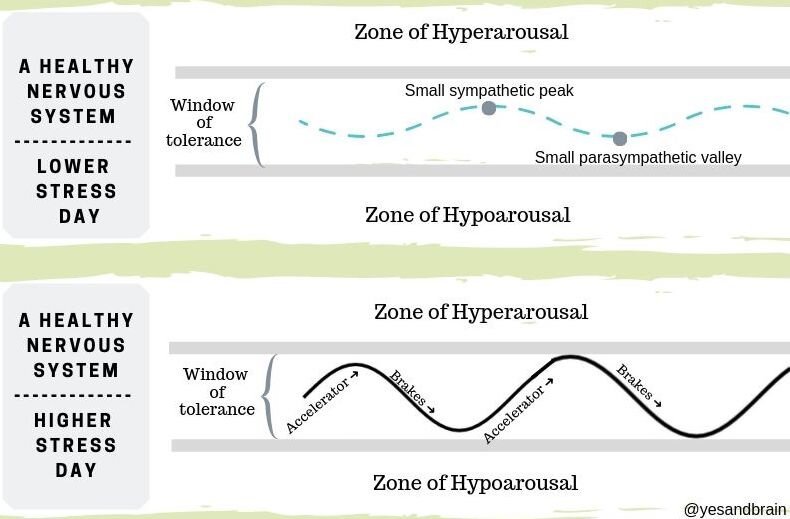

It is important that our systems know how to move between “danger responses” and “safety responses.” When we’re safe and calm, we need the ability to mobilize in the event of danger. And when we experience physiological responses to danger, we need to know how to get back to calm and social engagement when the risk is no longer present.

Functionally, play tends to trigger alternating neuroceptive cues that move us back and forth between danger and safety. This essentially means that we’re giving our brain a “neural workout” by letting it develop familiarity with moving between these two states in a safe environment.

As we move from “danger responses” back to “safety responses,” we reinforce our resiliency and train our brain to know that it can manage difficult moments and re-regulate when we encounter tough things both on and off the stage. This neural navigation improves the efficiency of the social engagement system to down-shift from fight/flight when needed.

Being able to identify and toggle between states is the fundamental element of regulating (the ability to monitor and modify) our affect, emotion, physiology, motor movement, communication, interaction with others etc. - which is why this is key. (K)

This process directly mirrors the Window of Tolerance, and the ways in which we experience acceleration and braking throughout the day, even when we’re not explicitly engaged in play. Coined by Dr. Daniel Seigel, the window of tolerance refers to the optimal zone of arousal where we can function, manage, and thrive. In simple terms - this is the zone in which we successfully handle the stressors of our daily lives without excessive emotional distress or engaging in maladaptive behaviors.

Let’s take a quick detour to break this down further.

Throughout each day, we encounter both stressors and soothing moments that activate an internal accelerator and braking system that dictates our level of arousal, and whether we stay in our window of tolerance - or not.

To give an example, imagine that you’re running late for a class. Your system is likely accelerating (sympathetic system) during the moments that you’re rushing and feeling anxious about your tardiness. Once you arrive and settle in, your brakes activate (parasympathetic system), and you’ll likely re-regulate to calm.

In an ideal world, our accelerator and braking systems will work in tandem throughout the day to keep us within our window of tolerance. If you have a healthy regulatory system, chances are good that you’ll stay within the window of tolerance a good portion of the time.

We all have moments when we move outside of our WOT, and may drop into hypo-arousal (zoned out, immobilized, dorsal vagal parasympathetic nervous system), or push into hyper-arousal (fight or flight, sympathetic nervous system).

It is important to note that our window of tolerance can change day to day (and even moment to moment). If you’re sick, tired, hungry, or any other number of things - you may find that your window of tolerance is narrower than it was the day before. This means that something that didn’t cause you significant stress yesterday could take you out of your WOT today.

As we learn to increase our awareness and re-regulate throughout the day, we have the opportunity of strengthening and expanding our window of tolerance. Because improv offers so many opportunities to experience small peaks and valleys within our nervous system response, we get to explore micro-toggling within a safe and connected setting.

Imagine when you first attended an improv class.

You likely felt nervous, and your sympathetic system almost definitely activated as you engaged in exercises that asked you to be flexible, engage in spontaneity, and trust your classmates. If you had a good teacher - they likely established a safe and supportive environment that progressively built up not only your improv skills, but also your ability to tolerate the emotional dysregulation that goes along with trying on these new skills. (Shout out to Shana Merlin - my first improv teacher & later mentor. - A true wizard when it comes to building progressive competency in both skill & emotional regulation).

When we first start improvising, it can sometimes feel impossible to think about “surrendering” to the present moment, and to deeply believe that you can trust both yourself - and others - to remain attuned in collaboration. Even simple exercises - like a word association game - can elicit worries about “not doing it right” or coming up with “good enough” contributions.

Though the stakes are actually low (really, nothing bad is going to happen if you freeze or don’t come up with a word), we can find ourselves sympathetically activated and anxious in these games.

As we anticipate our turn, our physiological arousal levels may increase, and then they subsequently decrease once we’ve completed the required task. As teachers successfully create safe spaces where students can push outside their comfort zones, they build neural resiliency that helps students re-regulate when demands are later increased.

Keep in mind that sympathetic activation in improv is not always in the form of stress or anxiety. Imagine a high-energy game like Kitty Wants a Corner, where players mischievously watch for openings to move quickly across the circle without being caught. Students may not feel particularly anxious as they make those moves, but their sympathetic system will activate as they mobilize to cross the circle, and then they’ll re-regulate into social engagement once they land in their new spot and share a moment of celebration with their spot-trading-partner.

There are certainly some games that engage this patterning more than others, but I’d argue that improv overall invites us to activate the social engagement system to repeatedly regulate out of fight/flight, which strengthens our overall resiliency.

2. IMPROV TEACHES SOCIAL/EMOTIONAL LEARNING (WHICH AGAIN REINFORCES SOCIAL ENGAGEMENT)

Though most people acknowledge that we’re largely social creatures who seek (and need) connection, the level of connection that we desire isn’t always easy to find, especially for those with trauma histories, developmental disorders, or mental health diagnoses. Social connection may not come naturally for some, or may even be avoided as a mechanism of self-protection from the vulnerability of being open with others. Improv is unique in the way that is offers progressive and safe opportunities to build relationships.

Many improv games invite students to bring themselves fully to the group and activity, but also provide various options of engagement that meet students where they are. I talk often about the fact that you can’t “break” improv, and that it can be adapted in just about every way imaginable.

For example, if a student isn’t ready to participate with the group on stage- that is okay. If they want to stand in the circle, but not say anything - also okay. If they never speak a word - I can work with that.

There is no end to the ways that exercises and games can be adapted to meet the needs of everyone, and to create a collective unity among the group - regardless of everyone’s modes of participation.

Improv pedagogy and exercises are inherently built around strengthening collaboration, connection, and communication skills - and social feedback can also be provided to students within the context of making changes to be a “better improviser,” rather than within the context of students being “successful” - or not - socially.

For example, a teen who struggles with listening to others can be provided direct and supportive feedback about the importance of listening within an improv scene - and can be guided through effectively accomplishing this on stage. Because this feedback is focused on “being a good improviser,” my anecdotal experience shows that this often results in a depersonalized (and improved) student-response, as it feels different than responses they’ve received in other settings that reinforce an idea that they’re socially inadequate.

Further, because scaffolded improv provides students with opportunities to find success in building social engagement at progressively sophisticated levels, improv often provides students with opportunities to feel success in a way that they may not often get to experience.

In turn, this reinforces the continued development of these skills.

Classes often start with a fairly low bar of players initially just “existing” in shared space with other classmates, then slowly build listening, flexibility, and spontaneity skills that enable students to respond more authentically to increasingly complex offers.

These systems strengthen our social engagement system (ventral vagal pathway), and as this is strengthened, it becomes easier for our systems to recall and activate this patterning (and find connection).

Even if you don’t identify as someone who struggles with social skills, chances are good that you feel like you’ve become a progressively better listener and responder in your improv classes. You’ve likely learned how to remain present in the moment, to attune to those around you, and to respond with relevant subject matter.

This is no surprise, as the foundational skill of “Yes Anding” in improv fundamentally mirrors the skills needed for successful dyadic conversational exchange - a core social emotional skill.

3. IMPROV GENERATES EMBODIMENT AND IMPROVED AWARENESS OF SELF & OTHERS

Most of us are not as in touch with ourselves or our bodies as we’d like (or need!) to be. Our nervous system has established pathways for how we move in the world, and these patterns are often on “autopilot” on an unconscious level. As we explore physical movement, try on different characters, consider how we feel about the process, and navigate connecting and sharing space with others - we invite integration - (the linking of differentiated elements), which means that we connect distinct modes of information processing into a functional whole.

During this processing, we modulate the information flow between our body and mind, which shapes the way that we think, feel, and behave (K). In interpersonal neurobiology, this integration is postulated to be the “fundamental mechanism of health” (L) - which is why this is so important.

When scaffolded correctly, improv systematically invites embodiment in our students.

Starting with simple exercises that orient students to the space (like “Come Over Here, If…”), we invite students to move around the room, share, listen, and understand themselves within the context of the group. As we build gradual connections with others, we shift our awareness from our own experience to a space of connecting and noticing others.

We’re taught to listen and acknowledge the offers we’re given. And through the practice of watching for - and accepting - offers made by others, we’re able to better understand and accept ourselves.

4. IMPROV PROVIDES US WITH AN OPPORTUNITY TO RE-WRITE THE STORY OF WHO WE ARE

As we move through the world, our body and minds collect stories, frameworks, and ideas about who we are. These schemas work below our conscious awareness, and inform the way we view the world. For example, if someone was repeatedly told that they’re worthless and that no one will ever love them, they’re likely to interpret what they encounter later in life through the expectation that they’re unloveable and without worth - and they’ll physiologically respond to situations accordingly.

While not everyone has received that type of feedback, we are all shaped by the experiences that we have had, and we’re not always fully aware of how our internal beliefs are influencing our perception and the way we navigate the world.

Improv provides us with a unique opportunity to play different characters who have different viewpoints, statuses, and strengths than our own. This “shakes up” our pre-determined pathways, and invites us to experience what it is like to be someone besides who we are.

Most of us have likely experienced feeling “stuck” at some point in our lives, and can relate to the idea that it isn’t always easy to make changes - even if we intellectually know that something isn’t working.

Improv invites students to move beyond intellectual consideration and to “try on” being someone other than who we are. And as we do this, we may open new understanding and find new ways of moving through the world that feel increasingly comfortable and accessible.

5. IMPROV PROVIDES RHYTHM, GROUP MOVEMENT & HEALING RELATIONAL ENGAGEMENT

While not as clearly rhythm based as some art forms, such as dance or circus, improv provides a significant amount of collective, patterned, repetitive, somatosensory, and relational activity, which is regulating for the lower parts of the brain. Because our systems are self-organizing and seek healing, (E) we use these experiences to re-organize and soothe the brain.

In turn, having a regulated lower brain impacts our overall emotional regulation and the way that we organize, understand, and interpret our internal system as we move through the world.

In utero and early life, we experience repeated rhythmic, relational, and somatosensory activity (gentle movement in utero as our mother moves, maternal heart rate, being rocked, moments of eye contact and co-regulation etc.) that reinforces a strong implicit sense of safety. When we engage in parallel activity later in life, we’re able to tap into strong implicit (unconscious) memories from our early experiences, which can unlock a new foundation of regulation. (H)

If you didn’t have these positive and safe experiences as a young child, improv may be a way for you to “re-claim” some of these rhythmic and relational engagements that your lower brain so desperately needs to regulate.

6. IMPROV IS REINFORCING

Pushing against our comfort zone can be challenging. Because improv is (often, hopefully!) fun, it reinforces our willingness to experience things that we might otherwise avoid due to discomfort. Because we’re willing to stay engaged in the improvisational process, we’re able to experience a significant number of practice repetitions that help us increase our window of tolerance, build affective connection with others, and practice collaboration in a way that activates our social engagement system.

Additionally, research has shown that we learn best when we’re engaged in experiential, multi- sensory learning experiences, and when we build on previous knowledge/areas of expertise. Improv provides us with all of these opportunities.

CONCLUSION:

Improv is regulating for our lower brain, and invites us to feel deeply, respond to relational information, expand our window of tolerance, strengthen our social engagement system, and to better understand and re-write the story of who we are and who we have the capacity to be.

Throughout this process of connecting our brain and our body, we feel uncomfortable and push through it.

We experience hundreds of rapid-fire repetitions of re-regulating, connecting, and leaning in towards others in social engagement.

We move into safe connection and curiosity with ourselves and others.

Our regulatory system further organizes and integrates.

We access our voice and teach our brain and our body to collaborate and effectively share information.

We become present & attuned.

And, that is why improv works.

-Lacy Alana, LCSW, RSW, MSSW

Want more? Join me for a four-week Applied Improv training series for Therapists!

A. The Polyvagal Theory - Neurophysiological Foundations of Emotions, Attachment, Communication, and Self-Regulation - Stephen W. Porges, 2011

B. Affect Regulation and the Repair of the Self - Allan N. Schore, 2003 - p. 152

C. Bloch-Atefi A., & Smith, J. - The effectiveness of body-oriented psychotherapy: A review of the literature. 2014 - PACFA, Melbourne.

D. The Polyvagal Theory: phylogenetic contributions to social behaviors, Stephen Porges, 2003, Journal: Physiology and Behaviors

E. The Body Keeps the Score - Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma - Bessel Van Der Kolk, M.D. - 2014

F. The Body Keeps the Score - Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma - Bessel Van Der Kolk, M.D. - 2014 p. 275, F2 - p. 355

G. The Feeling of What Happens: Body and Emotion in the Making of Consciousness, Antonio Damasio, New York:Harcourt, 1999

H. The Neurosequential Model of Therapeutics: Applying principles of neuroscience to clinical work with traumatized and maltreated children. - Bruce Perry

I. Social interaction moderates the relationship between depressive mood and heart rate variability: evidence from an ambulatory monitoring study. - 2009, NCBI

J. 2013 - Barbara Fredrickson & Bethany Kok of the University of North Carolina: “How Positive Emotions Build Physical Health: Perceived Positive Social Connections Account for the Upward Spiral Between Positive Emotions and Vagal Tone.”

K. Pocket Guide to Interpersonal Neurobiology: An Integrative Handbook of the Mind - Daniel Seigel - 2012

L. Pfeifer R. The Body Shapes the Way We Think: A New View of Intelligence. Cambridge: MIT Press; 2007.

M. Kyla Bourassa and colleges at Univ. Of Ariz. “The Impact of Narrative Expressive Writing on Heart Rate, HRV, andBlood Pressure following marital separation.” - 2017

N. Porges, 2015, Play as a neural exercise: Insights from the Polyvagal Theory Stephen W. Porges, PhD Department of Psychiatry

The Body Remembers:The Psychophysiology of Trauma and Trauma Treatment - Babette Rothschild

Neurobiology Essentials for Clinicians - What Every Therapist Needs to Know - Arlene Montgomery - 2013.

The Polyvagal Theory in Therapy - Deb Dana - 2019

Perry & Dobson, 2010: The role of healthy relational interactions in buffering the impact of childhood trauma.

Working with Children to Heal Interpersonal Trauma: The Power of Play, Guilford Press

Trauma and the Body: A Sensorimotor Approach to Psychotherapy (Norton Series on Interpersonal - Pat Ogden, Claire Pain, Kekuni Minton