The Science of Learning & Instructional Scaffolding in Circus Arts: The Tool You're Probably Using That You Need to Understand

(Want to learn more about circus, trauma, and what it actually means to be a Trauma Informed Coach? Check out my asynchronous course Check out my asynchronous course on trauma, the nervous system, and so much more! Click here to learn more!)

Why Scaffolding?

Understanding more about how the brain learns is useful for both teachers and learners. Many teachers share a foundational framework in scaffolding, and all teachers (to varying degrees) almost definitely use instructional scaffolding tools in their teaching.

In this article, I’ll explain how we learn, what instructional scaffolding is, why it matters, and how to integrate the concept into your own life (both relating to concrete tasks & emotional expansion). In the follow-up posts, I’ll introduce my own favorite (self-created) categories of scaffolding circus instruction, and will break down how to use that information - especially when it comes to emotional regulatory scaffolding.

This foundational article may teach you something new - or just help you put words to what you’re already doing!

How the Brain Learns

As Peter Levine notes, our brains are constantly in flux and “perpetually in a process of forming and reforming” (A) through the process that we call learning. This is “actually a process of importing the patterns, affects, behaviors, perceptions, and constructions recorded from previous experiences (memory engrams) to meet the demands of current encounters.” (A)

As we experience the world, connections (synapses) are made between neurons (brain cells), and as we increase or decrease engagement with certain things, our synaptic connections can strengthen or weaken. This changeability of the brain is called synaptic plasticity (or sometimes neuronal plasticity).

As we engage in learning and practice, we build more neuronal connections and thicken the myelin (layers of insulation that make information travel more quickly & protects the connections from erosion related to disuse) around existing connections.

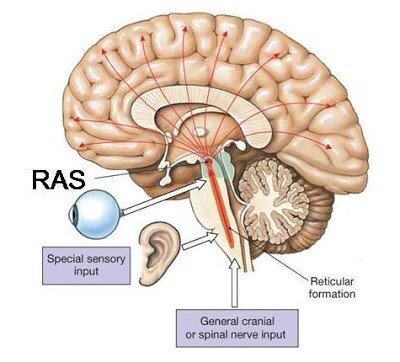

In a bit more detail (but still very simplified), we have sensory nerve endings in our muscles, joints, and organs that transmit constant “status reports” to our brain. A part of our brain called the Reticular Activating System (RAS) decides what our brain pays attention to by filtering out unnecessary information.

(Keep in mind that our brains are wired for survival, which means that it selects information that it deems to be most pertinent to the survival task. This is one reason why you may have a hard time focusing if you’re hungry, why an at-risk student may struggle to focus on learning tasks, or why you may struggle to execute complex skills if you’re feeling emotionally activated.)

After sensory information is selected to enter through the RAS, the amygdalae (a pair of structures within the limbic system - one on either side of the brain) determine whether the information is sent to the lower brain (more primitive, controls automatic functions like digestion/breathing/fight/flight etc.) or the upper brain (prefrontal cortex, memory/ storage/ thinking brain/where neural network guide voluntary behavior with reflective choices rather than reactive ones).

As our brain rapidly engages in this assessment, it also looks for patterns in what it is experiencing. The patterns it seeks are both related to the content being acquired AND how the process of learning is unfolding. This gives our brain information about where to channel our energy. For example, if we learn to expect a positive outcome from our efforts, our brain will encourage us to continue in the learning experience, and will find reward in that process (this is what is called a growth mindset).

On the other hand, if we come to believe that our efforts will not yield any results, we land in a “fixed mindset” - a coin termed by psychologist Carol Dweck (2007) - and we’re likely to disengage from the learning process. This, again, is a survival strategy. From a survival standpoint, it doesn’t make sense for you to continually expend energy towards something that isn’t yielding results, and our brain evolutionarily clusters information to deliver conclusions that save us time, energy, and resources.

Overall, this is very useful, but also means that we need to be mindful about the ways that we’re impacting our students when we’re teaching them, as we have the power to impact not only what they’re learning, but how they approach learning and expending efforts towards difficult tasks moving forward - which is a huge responsibility.

ONWARD FROM THE AMYGDALAE…

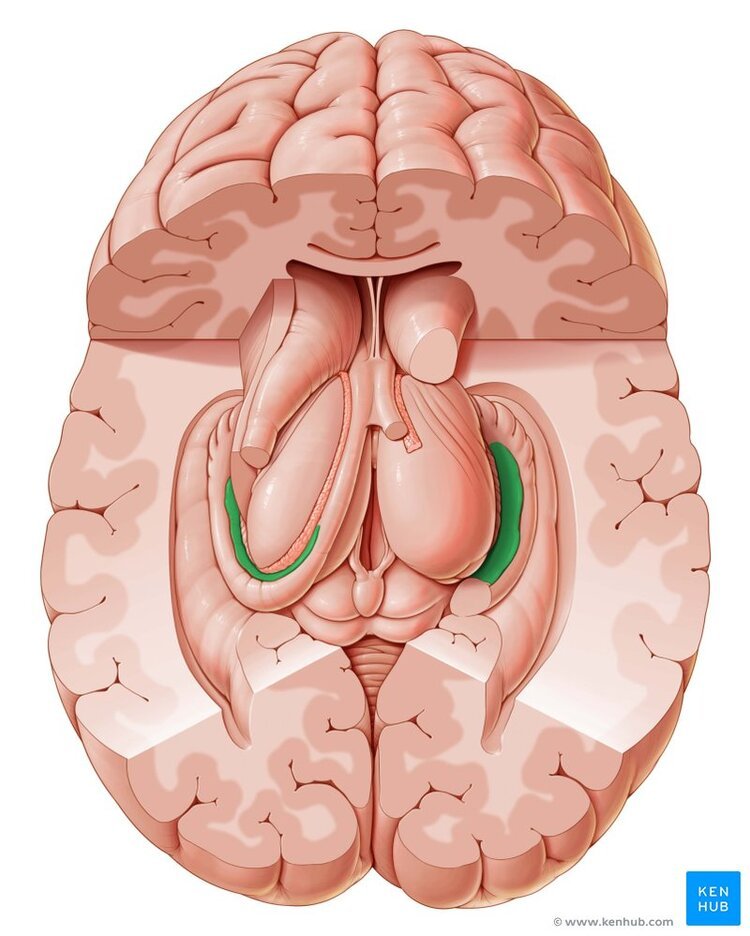

Once sensory information leaves the amygdalae, the hippocampi ( in the limbic system) play an important role in the formation and organization of new memories, and the linking of sensations and emotions to these memories.

Hippocampi - (in green) - Image from Kenhub.com

Upon entering the hippocampus, new information connects to existing pieces of relevant information, linking neurons together. These bits of information are then shipped off to different parts of the brain depending on the sensory modality of the encoded information (touch, hearing, vision etc.)

When our brain connects existing memory circuits, the brain (and these links) become stronger. This strengthening occurs either when the sensory modality is the same (i.e. smelling fresh-based cookies takes you back to grandma’s house), or when we learn through mixed somatosensory modalities.

This is why we learn better when teaching is experiential and includes blended learning - (i.e. it is better to mix verbal instructions and physical demonstration, or verbal instruction and kinaesthetic engagement than to just give verbal instructions).

This also tells us that students learn better when we’re building on relevant and prior knowledge, as we get to slot new bits of information into pre-existing “memory structures,” rather than building an entirely new framework. And, when the linkages are stronger, there is also a greater chance that they’ll be re-activated at a later date. (Seigel, 1999).

One final note: This learning process is also reinforced through dopamine, the brain’s “pleasure drug.” While it has many functions, for now, just note that dopamine is highly reinforcing. In response to pleasurable experiences, our brain releases dopamine, which feels good and drives us to repeat the things that caused the pleasure. When things are going well, and we feel motivated to keep going, this is a big part of why.

Important Take-Aways:

Our brains generate patterns to understand not only the content of what we’re learning, but how much energy we should expend towards the learning process. As educators, we have a responsibility to our students to be mindful about how we’re impacting our students’ drive towards learning.

Learning takes time. Even if someone gets a trick on the first attempt, they were able to do that based on previously established and connected neuronal structures. The more that we can build on those existing structures (and expand their breadth/depth), the better.

Dopamine reinforces good experiences, and dictates whether or not we return to keep trying something. This means that if we anticipate repeated failure during the learning process, we need to provide consistent positive reinforcement and measurable progress along the way to counteract the risk of sinking into a fixed mindset.

As we engage in learning, our brain rapidly links information together that coalesces into useable knowledge. Every act of recall is also potentially an act of modification (I). It is our job to figure out what our students know already, and how to help them move forward from where they are to the places they want to go. If we’re supporting our students to build progressive memory circuits, we’re leading them to mastery with less effort and more gain.

What is Instructional Scaffolding & How Does This Relate?

Scaffolding refers to supportive instructional techniques that are used to move students progressively towards skill mastery by providing assistance, adaptation, direction, or understanding that enables them to reach higher levels of success than they would reach independently. This often includes splitting a learning experience, skill, or concept into discrete parts, and then giving students tailored assistance to learn each part.

These supportive strategies are incrementally removed as mastery increases, and the teacher gradually shifts the learning process to the student. As this occurs, more advanced material can be integrated and introduced.

Scaffolding aims to increase positive emotions and self-perception throughout the learning experience by providing students with the opportunity to experience mastery, confidence, and success along the way -- rather than expecting them to jump from where they are to a place that doesn’t match their capabilities at the time.

Scaffolding can be used to teach concrete skills (climbing the silks, juggling), academic skills (multiplication), social emotional skills (dyadic engagement, emotional regulation), self-expression skills, mindfulness, and just about anything you can imagine!

Image from What to Expect

Many of us have intuitive experience with scaffolding skills, and this intuition can be harnessed to become a stronger teacher. A great example of this intuition can be seen when adults support babies as they learn to stand and walk. If a caregiver lifted a baby who doesn’t know how to stand independently into a standing position and expected them to stay standing when they released their grasp, the infant would fail at achieving the task of standing, and would almost certainly plop to the ground. With repeated trials, they might even develop fear, resistance, or displeasure to being placed into this position in anticipation of their coming failure.

However, a caregiver can scaffold this skill by holding a baby in a standing position, enabling them to kick their feet above the floor, slowly giving them more weight into their feet over time. They can help them strengthen their legs by supporting them as they explore this new position, and can slowly decrease the amount of support given until the child can stand independently.

Once the supports (the parent providing balance or taking weight, or the infant holding onto another object) are no longer needed, these supports can be removed, and the child will stand independently. The child will then take over a significant piece of the learning responsibility for strengthening their standing skills. From there, when the time is right, the caregivers can add new assists to advance the skill further (to walking, for example).

By now, you can likely see how this concretely relates to circus, and can recognize where you have experienced (or do) this.

Beyond scaffolding through physical supports (spotting lines, hand spotting etc.), we should also support learning and the emotional brain by using scaffolding to inform our curriculum development, skill progressions, teaching styles, and the way that we approach emotional regulation in the studio- which we’ll break down further.

Understanding how you’re already scaffolding - and how you can continue to expand this practice - can enrich your own training/emotional regulation, and that of your students. Understanding this framework can also help you troubleshoot any areas where you’re struggling or hitting a block. Today, we’ll primarily look at Skill-Driven Scaffolding.

Two more notes on scaffolding

By now, this is likely making great sense. You may feel like you do a great job of scaffolding already (hurray!), and you may also be curious about the different types of scaffolding - particularly related to emotional development & psychophysiological skill development, as discussed in previous articles.

We’ll get there!

When scaffolding circus skills, the amount of scaffolding provided should be in line with the current potential of the student in relation to the skill. It is important that we assess this potential in terms of both physical capability and emotional readiness.

More support (emotionally, instructionally, physically) should be offered when a task is challenging and difficult, while less can be offered as the student makes gains on achieving the task.

Two important things to keep in mind:

THE ZONE OF PROXIMAL DEVELOPMENT:

Lev Vygotsky, (1896 - 1934)

One construct that is helpful to consider when scaffolding instruction is Vygotsky’s concept of the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD) (G). This serves as a foundation of scaffolding, and describes the field between what a learner can do by themselves (expert stage), and what can be achieved with the support of an instructor or knowledgeable peer (pedagogical stage). Vygotsky was convinced that a child could be taught any subject efficiently using scaffolding practices.

Within this framework, students are lead through intentional learning activities that function as interactive conduits to help students advance to the next stage. For our students, we should aim to provide enough supports that they can be successful while acquiring new skills, followed by systematically removing the supports as students demonstrate new mastery.

LAGGING SKILLS & UNSOLVED PROBLEMS

Ross Greene (H), an American clinical child psychologist, pioneered an intervention that he calls Collaborative & Proactive Solutions. While this was not created with circus in mind at all, the takeaway from the model is relevant for our purposes, irregardless of the age of the student, or the completely different context. Bear with me, I promise I’ll bring it back to circus.

In a child psychology realm, Greene operated on the principle that no child wants to be the “bad kid,” and that if a child is struggling, there is a lagging skill and/or unsolved problem that is the culprit, and he created the Assessment of Lagging Skills and Unsolved Problems (ALSUP) checklist, accordingly. In child psychology, this means that when a child exhibits challenging behavior, it is evidence that the demands of the environment are exceeding their ability to respond adaptively.

In simple terms, this means that the child doesn’t have the necessary skills to handle the situation in a better way than they currently are. For example, imagine a child who got angry and punched another student. That is obviously less-than-ideal behavior, and the initial reaction of many will be to lean into punishing them for their behavior to “teach them” that it is wrong.

But we need to examine why it happened, or the opportunity for learning (and therefore actual change) is sold short. Chances are good that the child intellectually knows that punching another student isn’t a great choice, and that they may experience some consequences for doing it.

And yet, it happened.

If we take time to explore what lagging skills or unsolved problems remain, we might identify that this student is lacking emotional regulation skills or impulse control skills. We might identify that this child isn’t having their basic needs met at home (which means they’re activated in a survival space at unnecessary times). We might discover that this child has an expressive or pragmatic language disorder that impacts their ability to communicate their needs and feelings. And as we uncover these things, we now know where to start to actually address the child’s underlying needs. And we wouldn’t have solved the right problem if we hadn’t bothered to look for it.

Could we maybe have done something else to result in the child no longer hitting? Possibly. But, if the child is struggling with any of the needs listed here, the chances are good that the underlying problem will remain unsolved unless addressed.

It is the same in circus.

If your student (or you) can’t catch the dynamic skill, complete the inversion, or effectively sequence the newest trick your class is covering - we want to understand why, and address those challenges accordingly. Sometimes the reason isn’t as obvious as it seems.

(And, just like the child above, you might be able to find a shortcut to make things work for now, but if the underlying issue isn’t addressed, you better believe it is going to show up again).

While this seems obvious, this isn’t always how we approach ourselves. Messages that we give ourselves (or receive from others) can be loaded with ideas that if we just tried harder, we’d be able to do the thing. If we committed, or actually wanted it… we could do it.

And, sure, commitment is almost always useful, and practice builds neural connections that support learning. But, if you can’t do something, or you’re bailing on something…we need to understand why. Why is it hard to tap into commitment during that moment? What do you actually need to move forward? — Opportunities to practice discrete elements of that skill before linking them together? Encouragement to soothe your sympathetic system to reinforce that you’re safe? A different style of teaching? An opportunity to find success with smaller discrete skills so that you can re-activate your growth-mindset and start bridging things together? Something else?

It is easy to end up in a failure-loop when emotions are running high and we’re pushing outside of our comfort/current skillset. And when we’re given good instructions and we “know” what to do, and are still not having success, we have to dig deeper.

We’re not a failure - we just need scaffolding.

We need to first figure out where we are, and then figure out what exists in the gap between where we are and where we want to go. (And how we can progressively build the skills to get ourselves what we need - which doesn’t always unfold in a straight line).

If you’ve been following along with all my posts, you may also be realizing that this directly relates to the process of expanding our Window of Tolerance, which we’ll dive more into later.

Cool. Talk to Me About Putting Scaffolding Into Action.

Good news, bad news.

Bad news first: We’re about to reach the end of this article, and you’ll have to wait for the next one to dive deeper into concrete actionable tools that you can put into place and explore. I only have so much time in the week

Good news: I’m going to give you some homework assignments centered around Skill-Driven Scaffolding. (Also, welcome to my world, where “homework” is the good news.)

Pick your favorite skill. Make a list of everything you need to do that skill successfully. The list should be long. Even a really simple skill will have a long list. Imagine standing on a silks knot and leaning back. To do that, you need to be emotionally regulated enough to follow the steps safely, you need to know how high to hold the fabric, what grip to use, what part of your foot to put on the knot for the most stability, how to step off the ground with stability rather than pushing off and wildly swinging, how to engage your core, how to stay engaged while leaning back, how to return to standing successfully etc. The list goes on…and that is for a very simple skill. (If you want to get really intense about it, you can trace each of these skills back to another list of discrete skills needed to activate them. (I.e. grasping the silks requires wrist and finger strength, hand eye coordination etc.)

Identifying these things likely doesn’t feel magical, and it can even feel weird to do. However, the more that we can pro-actively turn our brain on to identifying the discrete components of successfully achieving a skill, the more likely we are to identify when something is going wrong, why it is happening, and where to go from there.

We don’t always appreciate what goes into something until we can’t do it. I had this driven home this year after having shoulder surgery and spending many months with no use of my right arm. There are so many things that our body does that we’re not really in touch with!

If you’re a particularly talented circus artist, your body may also automatically do things that feel miles away for others. Getting in touch with what your body is doing automatically will help your students tremendously when it comes time to break it down for them.

Identify where else you’re giving your brain the chance to practice the skills that you identified in number 1. Cross-reference and identify where else you use these skills when you train. Be curious about how you learned these skills, and how often they each show up in other things that you’re doing. Ask yourself how you could teach someone each skill you identified, and how you could best cue them, or break it down further if you needed to. (Are there other foundational skills they need to master before they will be successful with the one you’re thinking of?)

Turn your brain on to watch for scaffolding. Chances are great that you’re already scaffolding for yourself or your students. As you bring more awareness to this, it will also guide your ability to provide your students with “horizontal skill expansion” rather than “vertical skill expansion.” (i.e. giving your students new things to explore within their ability/to connect memory circuits with new/useful content, even if their technical ability or strength hasn’t increased).

Stay tuned for more!

Thank you for being here with me today!

-Lacy Alana, LCSW, RSW, MSSW

Want to learn more about circus, trauma, and what it actually means to be a Trauma Informed Coach? Check out my asynchronous course Check out my asynchronous course on trauma, the nervous system, and so much more! Click here to learn more!