The Window of Tolerance: A Psychophysiological Guide to Expanding Your Capacity as a Circus Artist (And Person)

This article is the second installment in a series that explores simplified interpersonal neurobiology that gives us a concrete way of understanding why circus works. Today’s blog will further explain the Window of Tolerance and how to use this information during your training or teaching.

If you haven’t read the first Article - Circus as a Healing Art: What Polyvagal Theory Teaches About Why Circus Works - it will provide a great foundational framework.

Want to learn more about circus, trauma, and what it actually means to be a Trauma Informed Coach? Check out my asynchronous course Check out my asynchronous course on trauma, the nervous system, and so much more! Click here to learn more!

WHY THIS TOPIC?

Whether you’re three classes deep into an intro series, or you’re a professional performer - you’ve undoubtedly experienced a wide range of psychophysiological (the intersection of physical and psychological) signals in response to the journey. If we can understand more about these signals, we can expand our regulatory and integrative capacity in and outside of the studio, keep ourselves emotionally and physically safe when we train, and learn when it is - and isn’t - the right time to keep pushing.

This is where the Window of Tolerance comes in.

WHAT IS THE WINDOW OF TOLERANCE?

Coined by Dr. Daniel Seigel, the window of tolerance refers to the optimal zone of arousal where we can function, manage, and thrive. In simple terms - this is the zone in which we successfully handle the stressors of our daily lives without excessive emotional distress or engaging in maladaptive behaviors.

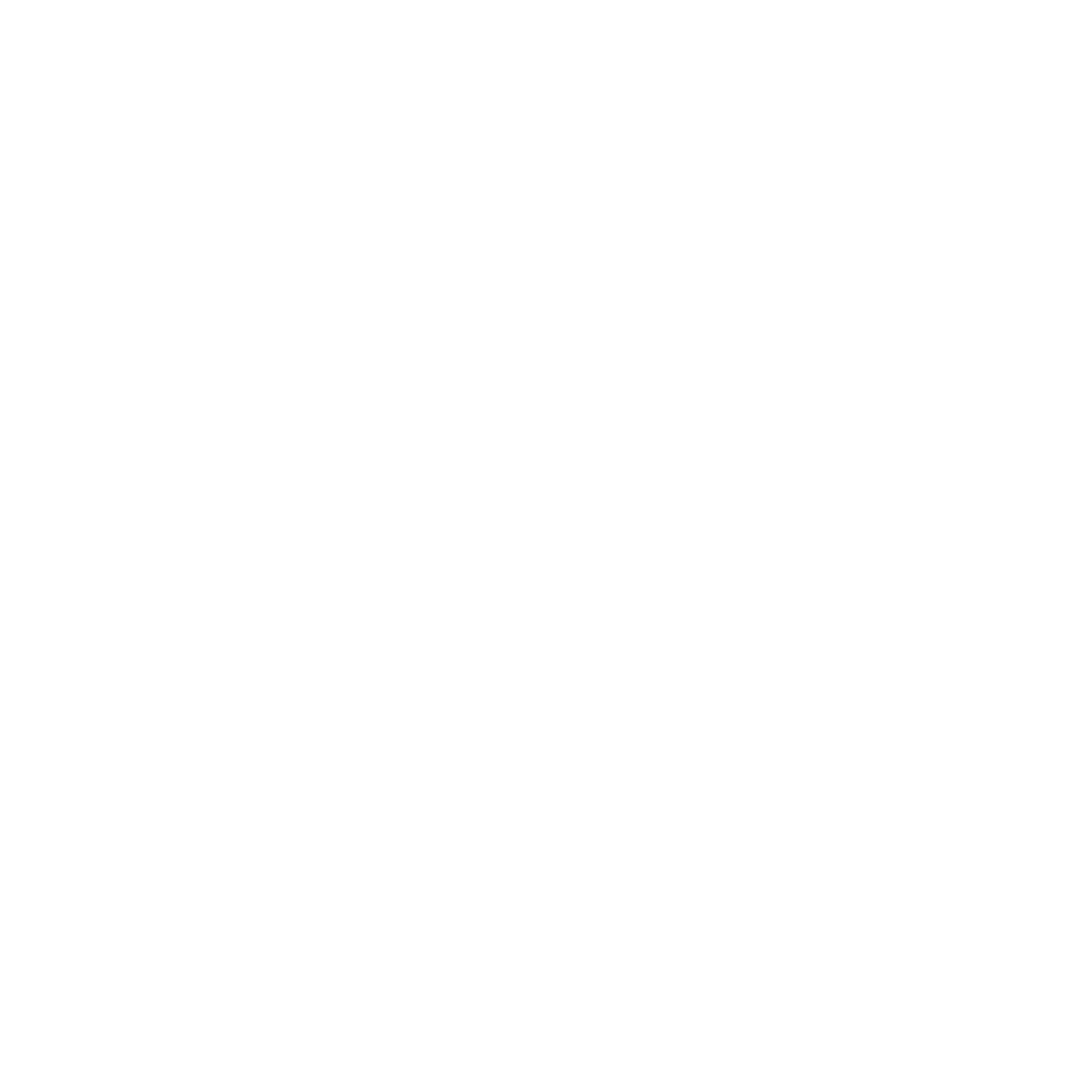

Throughout each day, we encounter both stressors and soothing moments that activate an internal accelerator and braking system that dictates our level of arousal, and whether we stay in our window of tolerance - or not.

To give an example, imagine that you’re running late for a class. Your system is likely accelerating (sympathetic system) during the moments that you’re rushing and feeling anxious about your tardiness. Once you arrive and settle in, your brakes activate (parasympathetic system), and you’ll likely re-regulate to calm.

In an ideal world, our accelerator and braking systems will work in tandem throughout the day to keep us within our window of tolerance. If you have a healthy regulatory system, chances are good that you’ll stay within the window of tolerance a good portion of the time.

We all have moments when we move outside of our WOT, and may drop into hypo-arousal (zoned out, immobilized, dorsal vagal parasympathetic nervous system), or push into hyper-arousal (fight or flight, sympathetic nervous system).

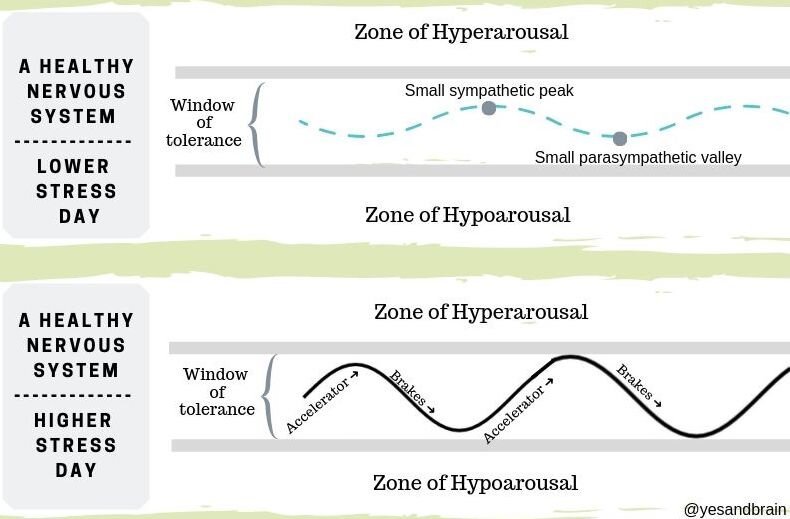

It is important to note that our window of tolerance can change day to day (and even moment to moment). If you’re sick, tired, hungry, or any other number of things - you may find that your window of tolerance is narrower than it was the day before. This means that something that didn’t cause you significant stress yesterday could take you out of your WOT today.

Additionally, the intensity of accelerating or braking is not objectively correlated to the activity at hand, and is instead dictated by the rhythm and patterning of your own nervous system and how your body has come to understand and react to the world. For one person, running late to a meeting may just cause a slight acceleration before they’re able to apply the brakes and re-center themselves, while for someone else, it might cause a huge spike in acceleration and throw them off balance for the entire day.

On this note, there are also other elements that can impact the way that your accelerator/brake system works, or how your window of tolerance changes. For example, if you have a mental health diagnosis or a trauma history, the way that your system responds to stress may not be as organized as the accelerator/brake arc above, and you may not have a cohesive strategy that helps you stay in your window of tolerance, despite intention and effort to do so. This type of patterning can be quite exhausting for a nervous system to manage, and you may perpetually feel like you’re just starting to get your bearings as things shift again.

The more that we understand about our personal systems, patterns, and tendencies, the better that we’ll be able to monitor - and modulate - where we are within our window of tolerance. By definition, this process is what it means to be able to regulate oneself. As we do this, we’ll be better able to more efficiently manage our energy, rather than having to recover from the further extremes.

(Keep in mind that this window of tolerance framework is a simplified view of the nervous system for the purpose of understanding some of our basic functioning. In reality, there are a number of miniature sections within the window, mixed states, and sub-phases of SNS and PSNS that activate as we slide through different phases and levels of activation. For our purposes, the simplified WOT will serve us well!)

COOL. HOW DOES THIS RELATE TO CIRCUS?

Circus provides us with a unique opportunity to explore, expand, and regulate our window of tolerance. In turn, increasing awareness of our WOT gives us a way to assess and monitor the safety and efficiency of our own training, and our emotional and physiological needs. As we do this regulation work, we move towards integration (the linking of differentiated elements), which means that we connect distinct modes of information processing into a functional whole. During this processing, we modulate the information flow between our body and mind, which shapes the way that we think, feel, and behave (C). In interpersonal neurobiology, this integration is postulated to be the “fundamental mechanism of health” (B) - which is why this is so important.

WHAT DOES THIS PROCESS LOOK LIKE IN A CIRCUS SETTING?

If you’ve ever been in a circus studio or taken a class, chances are good that you have felt a moment where your body/brain sent a strong internal signal that said “no thank you, please get down, I’m done now” — (or perhaps something with a similar sentiment, but more explicit phrasing). If this hasn’t happened for you - you’ve probably seen it happen for someone else.

With newer students, this often shows up when we explore climbing. A student may get halfway up the silks, freeze, and then announce that they’re coming down, despite the fact that they’re strong enough to make it to the top. Occasionally, this will be accompanied by them asking: “wait, how do I get down?” - even though they had previously been taught, had an intellectual understanding of the skills necessary to execute a safe descent, and might even already be safely descending the silk with appropriate technique while asking.

In moments like these, our systems are hijacked and overwhelmed with emotions (and the corresponding physical shifts) - and we can’t always access our thinking and problem-solving brain, or link our body and brain together in a useful and efficient way.

These are the moments when we’re pushing against our window of tolerance, or have perhaps crossed it, depending on the person and situation.

Keep in mind that we still may present as fairly “put together” during these moments where were pushing towards the edges of our WOT. Many of us have learned to hide, adapt, or ignore a lot of our internal signals, which may mean that we’re more dysregulated internally than we appear to be - or even cognitively know that we are.

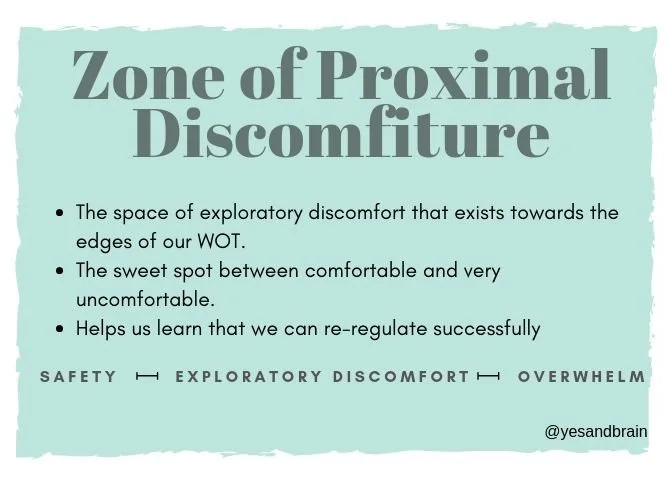

The Zone of Proximal Discomfiture

While we’re exploring our WOT in circus, we’re aiming for something called the Zone of Proximal Discomfiture - the sweet spot between feeling super comfortable, and feeling super uncomfortable.

This is the window of greatest growth and expansion of our WOT.

This often means that we are moving close to the edge of our WOT, but have not yet fully descended into hyper or hypo arousal.

We have to keep looking for this sweet spot, as this is a place of growth that still enables us to train safely, re-regulate psychophysiologically, and integrate the information that we’re processing.

In order to find it, we have to know where we are within our WOT, and what our body and brain signal to us when we’re there. In turn, these data points of awareness become our “roadmap” to guide us as we’re seeking training efficiency, safety, and regulation.

As we come to find the edges of this zone of proximal discomfiture (and re-regulate after visiting it, and while exploring it), our system begins to learn that it can handle the more challenging and dysregulating moments. Our regulatory bandwidth increases, and we learn that the peaks and falls associated with various states of arousal are tolerable and mobile. Through these repetitions, we learn to both passively experience - and actively engage - this modulation between states.

This is how circus helps us to integrate and become more adaptive, coherent, and stable.

Imagine the beginner student I mentioned earlier.

As they climbed higher on the fabric, their arousal increased (in direct correlation with their height on the fabric), and as they lowered themselves back towards perceived safety, their arousal decreased in parallel with their height from the ground. This student took themselves just far enough up the silks to challenge themselves without crossing a threshold into meltdown - and they found their zone of proximal discomfiture. (Stay tuned: Blog incoming about this parallel & regulating in circus by the incomparable therapist/wizard/aerialist Robyn Gobbel, LCSW).

Throughout this process, the silks climber had the experience of knowing themselves, listening to their needs, and getting in tune with their body. As they repeat this pattern, chances are good that their WOT will expand, and they’ll find themselves more comfortable with climbing higher. They have integrated information from the experience and intrinsically know that they have the ability to regulate as they complete this task.

Once this is known, it becomes recursive (the quality by which processes feedback on themselves to reinforce their own patterns of activation (B). This, in turn, becomes part of the fabric of their interpersonal psychophysiological system that informs how their brain and body respond to the people and things that they encounter on a daily basis.

Keep in mind that we frequently engage in this regulatory pattern of accelerating and braking without much intentional thought, as we often repeat behaviors that our body has discovered to be useful during times of dysregulation. For example, moving towards regulation might look like getting a drink of water, taking a bathroom break, or connecting with classmates to co-regulate etc. Remember that our systems are self-organizing and move towards this integrative understanding whenever possible, which means our bodies carry - and use - internal subconscious wisdom on a daily basis.

Even though the patterns of accelerating and braking often happen below conscious awareness, we have a lot to gain by putting our intention behind checking in with our system and identifying what tools we are using that help us re-center in our WOT. As we come to understand where we are - and what helps us stay in the middle of our WOT - we’ll be able to selectively apply our accelerator/braking system when we need to - both inside and outside of the studio.

There may be times that your system responds in panic, even when you are safe and physically okay. (Think: Some moments in flexibility training). Being in touch with where we are in our zone of proximal discomfiture - and learning how our body responds to the various stimuli it encounters - enables us to engage in micro-fine-tuning that will help us safely push ourselves further.

As we do this dance of pushing and re-regulating, we learn more about our WOT, and expand both our training and regulatory capacities.

HOWEVER…

Pushing through is not always what we need to expand our WOT. Think about a time that you were really stressed in your non-circus life, and you knew that you needed to rest, slow down, or take a break.

But you didn’t.

And suddenly, you got sick.

You knew your body needed a break and to rest. But when you didn’t give your body what it needed, it DEMANDED it.

Much like a toddler who isn’t feeling heard, our bodies will become louder and tantrum with more fervor if they don’t feel listened to. To avoid this type of relationship with our body, we have to lean in and listen to what it has to say.

If we don’t do this, and we push past the warning signs it is giving us, your body may double down, which could actually decrease our WOT, as your body will take steps that it thinks it needs to in order to protect itself. Accordingly, we want to send a message to our body that we hear it, want to listen, and that we deeply value the feedback and information it is giving to us.

While slowing down to listen more deeply to your body can feel counterintuitive, it is actually essential for efficient and safe training. We don’t learn well when we’re dysregulated, and if you keep trying to move forward while you’re not in a regulated space - you’re likely to work twice as hard for half as much gain.

On the other hand, if you take the time to regulate first, learn your system, and respond accordingly - your capacity for learning will increase - and you’ll serve yourself better in the long run.

Learning can take place if we do move deeply outside of our WOT, but it is often harder and more exhausting to work our way back into our WOT if we move far outside of it, and the potential risk for compromising our system increases as we move out of our WOT). For example, when we drop fully into our sympathetic (hyperarousal) and dorsal vagal (hypoarousal) pathways (outside of our WOT), Polyvagal Theory teaches us that we’re not able to fully activate and harness our thinking and problem-solving brain. This means that if we’re far enough into those states and still in the air or pushing ourselves on the ground - we could actually be putting ourselves at risk.

Don’t panic if you’re not sure where to start with applying this to your training or life. Over the next few weeks, I’ll be rolling out a series of short posts that delineate concrete tools that you can use to get in touch with your body, your WOT, and the data points that you can use to decipher your inner signals and needs. I’ll also break down what we can do as coaches to monitor and invite this awareness into our classes.

-Lacy Alana, LCSW,RSW, MSSW

Want to learn more about circus, trauma, and what it actually means to be a Trauma Informed Coach? Check out my asynchronous course Check out my asynchronous course on trauma, the nervous system, and so much more! Click here to learn more!

(A) Mindsight: The New Science of Personal Transformation Daniel Seigel , 2010 (book)

(B)Pocket Guide to Interpersonal Neurobiology: An Integrative Handbook of the Mind - Daniel Seigel - 2012

(C). Pfeifer R. The Body Shapes the Way We Think: A New View of Intelligence. Cambridge: MIT Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

Peter Levine & Dan Seigel in all the ways.